TITLE 18. PROFESSIONAL AND OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING

Title of Regulation: 18VAC85-21. Regulations Governing Prescribing of Opioids and Buprenorphine (adding 18VAC85-21-10 through 18VAC85-21-170).

Statutory Authority: §§ 54.1-2400 and 54.1-2928.2 of the Code of Virginia.

Public Hearing Information:

December 1, 2017 - 8:35 a.m. - Perimeter Center, 9960 Mayland Drive, Suite 201, Richmond, VA 23233

Public Comment Deadline: January 26, 2018.

Agency Contact: William L. Harp, M.D., Executive Director, Board of Medicine, 9960 Mayland Drive, Suite 300, Richmond, VA 23233, telephone (804) 367-4558, FAX (804) 527-4429, or email william.harp@dhp.virginia.gov.

Basis: Section 54.1-2400 of the Code of Virginia provides the Board of Medicine the authority to promulgate regulations to administer the regulatory system. In addition, the board is mandated to adopt regulations pursuant to § 54.1-2928.2 of the Code of Virginia, which was enacted in the 2017 Session of the General Assembly.

Purpose: The purpose of the regulatory action is the establishment of requirements for prescribing of controlled substances containing opioids or buprenorphine to address the overdose and addiction crisis in the Commonwealth. Reducing the quantity of opioids in the Commonwealth's homes and communities has already been shown to have a cost benefit and will ultimately have a direct public health, safety, and welfare benefit in a reduction in opioid misuse and opioid overdose deaths. The goal is to provide prescribers with definitive rules to follow so that they may feel more assured of their ability to treat pain in an appropriate manner to avoid under-prescribing or over-prescribing and thereby protect the public health.

Substance: The regulations establish the practitioners to whom the rules apply and the exceptions or non-applicability. Regulations for the management of acute pain include requirements for the evaluation of the patient, limitations on quantity and dosage, and medical recordkeeping. Regulations for management of chronic pain include requirements for evaluation and treatment, including a treatment plan, informed consent and agreement, consultation with other providers, and medical recordkeeping. Regulations for prescribing of buprenorphine include requirements for patient assessment and treatment planning, limitations on prescribing the buprenorphine mono-product (without naloxone), dosages, co-prescribing of other drugs, consultation, and medical records for opioid addiction treatment.

Issues: The primary advantage to the public is a reduction in the amount of opioid medication that is available in Virginia communities. A limitation on the quantity of opioids that may be prescribed should result in fewer people becoming addicted to pain medication, which sometimes leads them to turn to heroin and other illicit drugs. Persons who are receiving opioids for chronic pain should be more closely monitored to ensure that the prescribing is appropriate and necessary. A limitation on prescribing the buprenorphine mono-product should result in a reduction in the number of tablets that are sold on the street. The primary disadvantage to the public may be that more explicit rules for prescribing may result in some physicians choosing not to manage chronic pain patients in their practice.

The primary advantage to the Commonwealth is the potential reduction in the number of persons addicted to opioids and deaths from overdoses. There are no disadvantages.

Department of Planning and Budget's Economic Impact Analysis:

Summary of the Proposed Amendments to Regulation. Pursuant to Chapters 2911 and 6822 of the 2017 Acts of Assembly, the Board of Medicine (Board) proposes a permanent regulation for the prescription of opioids in the management of acute and chronic pain. This proposed regulation also sets rules for the use of buprenorphine in treating pain and, separately, as part of addiction treatment.

Prior to this, the Board promulgated an emergency regulation that became effective on March 15, 2017, followed by an amended emergency regulation that became effective on August 24, 2017. The emergency regulation is currently set to expire on September 14, 2018.

Result of Analysis. There is insufficient data to accurately compare the magnitude of the benefits versus the costs.

Estimated Economic Impact. The Board reports that this regulation is being proposed to "address the opioid abuse crisis in Virginia." Prior to the legislation enacted by the 2017 General Assembly, no regulations existed for opioid treatment of acute or chronic pain. In March 2017, Chapters 291 and 682 of the Acts of the Assembly became law. Acute and chronic pain are defined in the proposed regulation as follows:

• Acute pain, is "pain that occurs within the normal course of a disease or condition or as the result of surgery for which controlled substances may be prescribed for no more than three months."

• Chronic pain, is "nonmalignant pain that goes beyond the normal course of a disease or condition for which controlled substances may be prescribed for a period of greater than three months."

Each Chapter requires the Board of Medicine to promulgate regulations for prescription of opioids. For the treatment of acute pain, these Chapters require that the Board's regulation include:

(i) requirements for an appropriate patient history and evaluation, (ii) limitations on dosages or day supply of drugs prescribed, (iii) requirements for appropriate documentation in the patient's health record, and (iv) a requirement that the prescriber request and review information contained in the Prescription Monitoring Program in accordance with § 54.1-2522.1.

For the treatment of chronic pain, the Chapters require the regulations to include the requirements listed above for acute pain treatment, as well as requirements for:

(i) development of a treatment plan for the patient, (ii) an agreement for treatment signed by the provider and the patient that includes permission to obtain urine drug screens [UDS], and (iii) periodic review of the treatment provided at specific intervals to determine the continued appropriateness of such treatment.

Chapters 291 and 682 also require that the Board's regulations include rules for:

the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of addiction, including a requirement for referral to or consultation with a provider of substance abuse counseling in conjunction with treatment of opioid dependency with products containing buprenorphine.

This proposed regulation will apply to all doctors and physician assistants. However, it will not apply to: (1) the treatment of acute and chronic pain related to cancer or to such pain treatment for patients in hospice care or palliative care, (2) the treatment of acute and chronic pain during a hospital admission, or in nursing homes or assisted living facilities that use a sole source pharmacy or (3) a patient enrolled in a clinical trial authorized by state or federal law.

Requirements in the Proposed Regulation

Requirements for Acute Pain Treatment. For the treatment of acute pain, the Board proposes to require that the doctor or physician assistant: (1) take a patient history, (2) perform a physical examination appropriate for the complaint, and (3) assess the patient's history and risk of substance misuse. The Board also proposes to limit opioid prescriptions for all non-surgical acute care to a seven-day supply unless extenuating circumstances are clearly documented. For opioids prescribed as a part of a surgical procedure, the Board proposes to limit such prescriptions to a 14 day supply within the perioperative period3 unless extenuating circumstances are documented. The Board also proposes to set record-keeping requirements for acute pain to include a description of the pain, a presumptive diagnosis, a treatment plan, and information on medication prescribed or administered.

Requirements for both Acute and Chronic Pain Treatment. In treating acute or chronic pain, the Board proposes four requirements. First, practitioners will be required to consider nonpharmacologic4and non-opioid treatments5 "prior to treatment with opioids." Second, practitioners will be required to query the state's Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP). For acute pain treatment, this will occur before prescribing an opioid; for chronic pain, this will occur prior to beginning treatment and at least every three months thereafter. Third, the Board proposes to require that, "practitioners shall carefully consider and document in the medical record the reasons to exceed 50 MME/day"6 if they prescribe opioids in excess of that daily dosage, and to require that, "prior to exceeding 120 MME/day, the practitioner shall document in the medical record the reasonable justification for such doses or refer to or consult with a pain management specialist." Fourth, practitioners will be required to prescribe naloxone7 "when risk factors of prior overdose, substance misuse, doses in excess of 120 MME/day, or concomitant benzodiazepine is present." Practitioners also will be required to limit co-prescribing of drugs that may increase the risk of accidental overdose when taken with opioids.

Requirements Solely for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. For treatment of chronic pain, the Board proposes to specify medical record-keeping requirements. The Board also proposes to require signed patient agreements and urine or serum drug testing "at the initiation of chronic pain management and at least every three months for the first year of treatment and at least every six months thereafter." Practitioners also will be required to regularly evaluate patients for opioid use disorder and to initiate treatment for opioid use disorder or to refer the patient for evaluation and treatment if opioid use disorder is diagnosed.

Requirements for Treatment with Buprenorphine. The Board proposes four requirements for the prescribing of buprenorphine. First, the Board proposes to specify that buprenorphine is not to be used to treat acute pain in an outpatient setting except when a prescriber obtains a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration waiver and is treating pain in a patient whose primary diagnosis is the disease of addiction. Second, the Board proposes to ban the use of buprenorphine mono-product8 in pill form for treating chronic pain. Third, the Board proposes to ban the use of the mono-product to treat addiction except: (1) for pregnant women, (2) when converting a patient from methadone or the mono-product to buprenorphine containing naloxone (limit of seven days), (3) in formulations other than tablet form for indications approved by the FDA, and (4) for up to three percent of any prescribers' addiction patients who have a demonstrated intolerance to naloxone. Fourth, the proposed regulation would also limit dosages of buprenorphine and the co-prescribing of certain other drugs with buprenorphine, as well as require PMP queries for addiction patients.

Benefits and Costs of the Proposed Regulation. The requirements in the proposed regulation appear to confer a mix of benefits and costs, including those resulting from the mandatory use of drug testing, restrictions on the use of buprenorphine, preferences for non-opioid treatments, and use of the PMP. Except for the estimated costs directly resulting from mandatory drug testing, there is insufficient quantitative data to accurately determine, and thus compare, the magnitude of direct benefits versus direct costs. In part this is because the scope and range of potential impacts (cost and benefit) cannot be readily identified. To the extent that the proposed regulation reduces the rate of prescription substance misuse, including drug addiction, savings or cost avoidance could be achieved from reduction in expenditures on the treatment of, and consequences from, substance misuse.9 However, to the extent that the regulations create a disincentive to obtaining, or limit access to, opioid therapy, any savings or cost avoidance may be offset by direct and indirect costs resulting from untreated pain10 or a shift to illicit drugs.11

Direct Benefits and Costs of Drug Testing. Drug testing, typically through a urine drug screen (UDS) appears to confer direct benefits on all patients, although it is likely that a subset will receive higher benefits. As noted in the literature,

Pain management is a critical element of patient care. Over the last 2 decades the emphasis on managing pain has led to a substantial increase in the prescription of opioids. While opioids can significantly improve the quality of life for the patients, there are many concerns.... Therefore, monitoring adherence for patients on (or considered candidates for) opioid treatment is a critical element of pain management…. Of the various tools, UDS is perhaps the most effective in detecting non-adherence, and is viewed as the de facto monitoring tool.12

There are two main types of UDS: immunoassay testing ("dipstick") and chromatography (i.e., gas chromatography/mass spectrometry [GC/MS] or high-performance liquid chromatography). Both types of UDS can assist practitioners in creating initial treatment plans and also indicate when adjustments are required throughout the course of treatment. In addition, testing can be used to monitor drug elimination rates and ensure that a steady state of the prescribed drug has been achieved. Furthermore, non-prescribed drugs can be identified and appropriate actions taken, including referral for substance use disorder. Monitoring urine toxicology also can help practitioners comply with federal Drug Enforcement Agency requirements, which require practitioners to minimize abuse and diversion.13 However, quantitative data on the value of these benefits does not appear to be readily available. Moreover, full realization of the benefits of UDS may require both types of test: an initial immunoassay test in a practitioner's office followed by a confirmatory GC/MS test in a laboratory.

In order to quantify the costs of drug testing, the number of patients who will likely be affected by urine testing requirements must be estimated. The Board did not provide estimates of the number of patients affected, so estimates from relevant literature on the prevalence of chronic pain were considered. Estimates of the percentage of the population affected by acute pain do not appear to be readily available.

Using information taken from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), National Institutes of Health staff estimated that 11.2 percent of the adult population experiences chronic pain—that is, they had pain every day for the preceding three months.14 In Virginia, using 2016 Census Bureau data on population by age, this equates to 732,669 adults. On the high end, the Institutes of Medicine (IOM) report that common chronic pain conditions are prevalent among 37 percent of adults, "amounting to approximately 116 million adults in 2010—a conservative estimate as neither acute pain nor children are included."15 This equates to approximately 2.4 million adult Virginians.

Although these two estimates may indicate the extent of chronic pain among adults, they may not indicate the extent to which persons with chronic pain seek opioid therapy. A low-end estimate is supported by at least one study (Boudreau, et al, 2009),16 that indicates that 3 to 4 percent of the adult population were prescribed longer-term opioid therapy.17 (Note: to the extent that opioid prescription rates have increased since this study was conducted, this estimate would be too low.)

These three estimates will be used to estimate the potential number of adults in Virginia who could be affected by the proposed regulation (Table 1). Using these population estimates, and the Board's estimate that the average cost of an initial "dipstick" UDS is $50, direct costs of the new requirements for the initial UDS would likely be between $12 million and $141 million for the initial screen, assuming all persons with chronic pain seek opioid therapy. Subsequently, the annual cost for four quarters of drug tests would be between $57 million and $605 million, assuming all persons with chronic pain seek and continue to receive opioid therapy for a full year. To the extent these assumptions are not borne out, the cost would decrease. After the first year, these costs would decrease as patients shift from quarterly to biannual testing.

|

Table 1

|

|

Potential Ranges of Persons with Chronic Pain

|

Estimated Number of Adult Virginians with Chronic Pain

|

Cost of Initial Test *

|

Additional Cost of All First Year

Quarterly Tests *

|

|

Boudreau et al (3.5%)

|

228,959

|

$12 million

|

$57 million

|

|

NHIS estimate (11.2%)

|

732,669

|

$37 million

|

$183 million

|

|

IOM estimate (37%)

|

2,420,423

|

$121 million

|

$605 million

|

|

* Assumes 100 percent of all persons with chronic pain within each of the three estimates are treated with opioids.

|

These estimated costs may potentially increase to the extent that testing is repeated because practitioners account for the possibility of unexpected drug screen results, such as false positive and false negative results in the immunoassay or "dipstick" test typically used in a practitioner's office.18 A false positive result occurs when the test result is "positive" but the indicated substance is not actually present. A false negative occurs when the test fails to indicate the presence of substances that are actually present. These and other unexpected results that could prompt re-testing could occur for a variety of reasons, including failure to take the prescribed medication, testing error, metabolic differences, and drug interactions. Brahm et al. notes that false positive opiate results have been reported for certain antibiotics (quinolones and ofloxacin).19 Although re-testing is recommended, it may have unintended consequences:

the use of medications with the potential for false-positive UDS results may present a significant liability for individuals required to undergo random or periodic UDSs as a component of a recovery or court-ordered monitoring program or as a condition of employment. In addition, false-positive UDS results may affect the clinician–patient relationship by raising issues of trust.20

As noted in the literature, "the interpretation of opioid testing results is far less straightforward than many health care providers who utilize this testing appreciate."21 There are two main types of urine drug screening: immunoassay testing and chromatography (i.e., gas chromatography/mass spectrometry [GC/MS] or high-performance liquid chromatography). Immunoassay tests use antibodies to detect the presence of drugs. These tests can be processed rapidly, are inexpensive, and are the preferred initial test for screening.22 When urine tests have unexpected results, the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends23 that a, "confirmatory test using a method selective enough to differentiate specific opioids and metabolites (e.g., gas or liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry) might be warranted."24 Although these tests can cost several hundred dollars or more, they are the forensic criterion standard means of confirming initial screening tests because they have a low incidence of false positive results and are very sensitive and specific.25 Board staff referred to the CDC Guideline, and also stated that the treatment agreement signed by the patient would indicate the actions to be taken if unexpected results cannot be explained.

Indirect Benefits and Costs of Drug Testing. The use of drug screens appears to have a mix of benefits and costs. As noted by the CDC Guideline, practitioners should use unexpected results to improve patient safety. This could include several strategies that, if properly designed and applied, would appear to confer this benefit. Examples of responses to an unexpected drug screen result include a change in pain management strategy, tapering or discontinuing opioids, more frequent re-evaluation, offering naloxone, or referring for treatment for substance use disorder. The CDC notes that practitioners:

should not dismiss patients from care based on a urine drug test result because this could constitute patient abandonment and could have adverse consequences for patient safety, potentially including the patient obtaining opioids from alternative sources and the clinician missing opportunities to facilitate treatment for substance use disorder.

Board staff appear to agree with this guidance, adding that a patient could also be released from care if they do not comply with the treatment plan.26 The Board has also stated that patients should not be abandoned. As noted in a letter from the Board to practitioners:

As you consider these regulations, make sure that the needs of patients currently receiving opioids for chronic pain are taken into account. It is critically important that no patients in Virginia find themselves looking for narcotics outside of the medical system – i.e., on the street.27

However, as documented in some of the available literature, the use of drug screens may create a disincentive for certain patients to continue seeking treatment and thus may stop pursuing opioid therapy.28 Moreover, Board staff also acknowledge that the drug testing and other requirements in the proposed regulation will create disincentives for primary care physicians to treat pain using opioid therapy. And given that the Board has stated that the regulation is, in part, designed to "provide the board with a tool to discipline physicians whose practices do not meet the standard of care,"29 the regulation may cause some primary care physicians to no longer treat chronic pain patients with opioids.

In addition, examples of some recent literature notes that, "individuals who lost access [to prescription opioids] have turned to cheaper, more accessible, and more potent black market opioid alternatives—including heroin—in unprecedented numbers."30 Thus an additional unintended consequence of the regulations may be a shift in demand from legal prescriptions to illegal street drugs, including heroin and fentanyl (in combination or separately). As noted in a recent issue of the International Journal of Drug Policy, "prescribing restrictions forced a minority of dependent users to more potent and available street heroin."31 The federal Drug Enforcement Administration notes that "fentanyl can serve as substitute for heroin in opioid dependent individuals."32

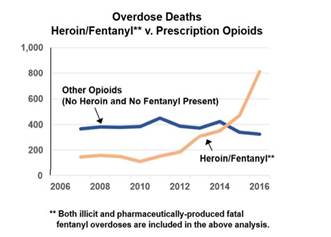

As noted by the Board, "the purpose of the regulations" is in part "to assist physicians in treating opioid dependent patients."33 However, to the extent that some patients, particularly those with substance use disorder, no longer obtain treatment, they may seek illicit substances. It is not clear if this is occurring in Virginia, but data released by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) indicate that "there has not been a significant increase or decrease in fatal prescription opioid overdoses" from 2007 to 2016, but "fatal fentanyl overdoses increased by 176.4% from 2015 to 2016."34(This trend is illustrated in the figure below.) Although it does not appear that the OCME can determine whether the fentanyl was illicit or pharmaceutically-produced, staff at the Department of Forensic Science (DFS) report that over the last 12 years submissions of prescription fentanyl have averaged between 25 and 27 samples per year. In contrast, data reported by DFS indicate that the number of submissions of illicit fentanyl increased by 1,656 percent from 2013 to 2016.35

Indirect Benefits and Costs of Restrictions on Use of Buprenorphine. The Board's proposed restrictions on the use of buprenorphine are aimed at decreasing the abuse of the mono-product of this drug ("Subutex") because it has become a popular drug of abuse. To the extent the proposed regulation decreases abuse, then a benefit will be conferred. However, any decrease in the abuse of this drug attributable to these proposed restrictions would need to be weighed against the costs that may accrue for chronic pain patients and individuals in addiction treatment.

Board staff reports that the cost of Suboxone (which contains buprenorphine plus naloxone) is higher than the cost of Subutex. To the extent, therefore, that certain patients are no longer able to obtain prescriptions for Subutex, then they will likely incur increased costs. As noted by Board staff, demand for opiates is highest in the places where health insurance coverage is lowest. Therefore, these cost increases may disproportionally fall upon patients who pay for prescriptions (and drug screens) out of pocket. Additionally, it is reported that some portion of the general population has an allergy or sensitivity to naloxone and would not be able to take Suboxone.

In response to concerns raised about restrictions on prescription of the mono-product that did not account for individuals who had an allergy or sensitivity, as well as the ability to pay, the Board voted to allow treatment with the mono-product for up to three percent of any prescribers' addiction patients who have a demonstrated intolerance to naloxone. This allowance was made for individuals in addiction treatment but not for chronic pain patients (who presumably would have the same incidence of Naloxone allergies). The Board believes that this three percent allowance will be sufficient to cover the portion of addiction patients who have a true allergy/insensitivity. These individuals are not likely, however, to be evenly spread among all doctors. This means that some doctors may have more than three percent of their patients for whom the mono-product would be the preferred treatment and some may have less. Because of this, some patients and practitioners may see disruptions in treatment.

Indirect Benefits and Costs of Preferences for Alternative Treatments. The proposed regulation's requirements that alternative treatments (both nonpharmacologic and non-opioid) be given consideration prior to prescription of opioids for both acute pain and chronic pain is being proposed to reduce the number of such prescriptions. Board staff state that nonpharmacologic treatments may include physical therapy, chiropractic, and acupuncture.

In addition, non-opioid treatments can include treatment with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as well as selected antidepressants and anticonvulsants. Although these drugs do not have the addiction risks of opioids, they may pose other health risks for certain patients. As noted by the CDC Guideline, although NSAIDs are recommended as first-line treatment for osteoarthritis or low back pain they do have risks, including gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation as well as renal and cardiovascular risks. Increasing use of non-opioid treatments like NSAIDs will therefore need to balance the benefits of non-opioid therapy with these and other risks.

Indirect Benefits and Costs of Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) Queries. Virginia statute presently requires PMP checks for any prescriptions anticipated to be used for more than seven consecutive days. The proposed regulation adds to the statutory requirements, and proposes to require that PMP queries be run for all individuals who are prescribed opioids. Board staff reports that some hospitals already require PMP queries for prescriptions issued in the emergency rooms (ER). Other hospitals that do not currently have this policy will likely accrue staff time costs. To the extent that use of the PMP lowers the volume of drugs diverted from licit to illicit uses, the new requirement will provide the benefit of reductions in the costs of illicit drug use in the state.

Indirect Benefits and Costs of Record-Keeping Requirements. The Board's proposed record-keeping requirements for acute pain are likely already common medical practice; thus licensees are unlikely to incur any costs from that portion of the proposed regulation that covers the treatment of acute pain. Likewise, most of the proposed requirements for taking a patient history and assessing a patient's complaint are likely common practice now and should not cause any additional costs. The proposed requirement that doctors in an acute care setting perform a risk assessment for substance misuse36on all patients who may be prescribed opioids may not presently be a part of standard patient care. To the extent that doctors treating acute pain do not currently assess risk of substance misuse, costs would be incurred for their time to perform such assessments.

Businesses and Entities Affected. These proposed regulatory changes will affect all doctors of medicine, osteopathic medicine, and podiatry as well as physician assistants. These proposed regulations also will affect all patients (both acute care and chronic care) who have been treated with opioids since the emergency regulation went into effect, and all patients who may be treated with opioids in the future. Additionally, individuals in treatment for addiction who are prescribed buprenorphine will be affected. Health insurance providers also will be affected. Board staff reports that the Board currently licenses 38,646 doctors of medicine, 3,117 doctors of osteopathic medicine, 616 doctors of podiatry, and 3,647 physician assistants. The Board has no estimates of the number of chronic pain patients that might be affected by this proposed regulation. Based on estimates of the number of the American adults who suffer from common chronic pain conditions, it is likely that this proposed regulation will affect at least hundreds of thousands of chronic care patients in Virginia and may affect as many as several million.

Localities Particularly Affected. No locality likely will be affected by these proposed regulatory changes.

Projected Impact on Employment. There is no apparent impact on employment. To the extent that the regulation reduces rates of addiction, productivity would increase.

Effects on the Use and Value of Private Property. There is no apparent impact on the use and value of private property.

Real Estate Development Costs. These proposed regulatory changes are unlikely to affect real estate development costs in the Commonwealth.

Small Businesses:

Definition. Pursuant to § 2.2-4007.04 of the Code of Virginia, small business is defined as "a business entity, including its affiliates, that (i) is independently owned and operated and (ii) employs fewer than 500 full-time employees or has gross annual sales of less than $6 million."

Costs and Other Effects. Based on Virginia Employment Commission data, there are 4,757 offices of physicians with fewer than 500 employees in the Commonwealth, thus likely qualifying as small businesses. These firms likely will incur increased costs associated with bookkeeping, staff wages, increased documentation requirements, and new drug testing requirements for chronic pain patients in the proposed regulation. Alternatively, adherence to the practices required by the regulation may have an unknown impact on liability insurance and associated costs that may result in savings.

Alternative Method that Minimizes Adverse Impact. There is no apparent alternative method that would minimize impact and achieve the purpose of the regulation.

Adverse Impacts:

Businesses. Doctors who practice independently may incur changes to current business practices related to increased bookkeeping, staff impacts associated with increased documentation requirements, and implementation of new drug testing requirements for chronic pain patients in the proposed regulation.

Localities. Localities in the Commonwealth are unlikely to see any adverse impacts from these proposed regulatory changes.

Other Entities. Chronic pain patients, or their insurance providers, may incur large annual costs on account of drug testing requirements and on account of restrictions on the prescription of buprenorphine mono-product that are in the proposed regulation. The Commonwealth of Virginia may incur increased costs on account of these proposed regulatory changes, including employee health benefits. The Department of Corrections may incur increased costs for drug testing and limitations on prescribing of Buprenorphine for prisoners housed in prisons statewide, and the Department of Medical Assistance Services may incur increased costs for Medicaid patients who are in treatment for chronic pain or who are undergoing addiction treatment with Buprenorphine.

References:

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK91497/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK91497.pdf.

Krishnamurthy, Partha, Govindaraj Ranganathan, Courtney Williams, Gulshan Doulatram. 2016. Impact of Urine Drug Screening on No Shows and Dropouts among Chronic Pain Patients: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Pain Physician. 19. 89-100. http://www.painphysicianjournal.com

/current/pdf?article=MjUyNA%3D%3D&journal=94.

Nahin, Richard L. "Estimates of Pain Prevalence and Severity in Adults: United States, 2012." The journal of Pain?: official Journal of the American Pain Society 16.8 (2015): 769–780. PMC. Web. 19 Sept. 2017.

Pollack, Harold, Sheldon Danzinger, Rukmalie Jayakody, Kristen Seefeldt. 2001. Drug Testing Welfare Recipients — False Positives, False Negatives, Unanticipated Opportunities.

Virginia Departments of Forensic Science and Criminal Justice Services. 2016. Drug Cases Submitted to the Virginia Department of Forensic Science Calendar Year 2016. http://www.dfs.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017

/07/CY16DfsDataReport_Final.pdf.

Virginia Department of Health Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. 2017. Fatal Drug Overdose Quarterly Report First Quarter 2017. Edition 2017.1. http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Fatal-Drug-Overdoses-Quarterly-Report-Q1-2017_Updated.pdf.

Dowell Deborah, Tamara M Haegerich, Roger Chou. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States. 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1.

____________________________________________

1http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?171+ful+CHAP0291.

2http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?171+ful+CHAP0682.

3Perioperative is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "a process or treatment occurring or performed at or around the time of an operation."

4These treatments can include such things as physical therapy, chiropractic care, and acupuncture.

5The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain indicates that nonpharmacologic and non-opioid treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy, interventional treatments, multimodal pain treatment, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants.

6MME is an abbreviation for morphine milligram equivalent, which provides a standard value for equating the potency of different opioids.

7Naloxone, sold under the brand name Narcan among others, is a medication used to block the effects of opioids, especially in overdose.

8Buprenorphine comes in two forms: the mono-product form of buprenorphine only contains buprenorphine and is sold under the name Subutex. The other form of buprenorphine also contains naloxone, and is sold under the brand name Suboxone. The mono-product is more subject to abuse, but a certain unknown portion of the population has an allergy/sensitivity to naloxone and therefore would not tolerate Suboxone.

9Florence, Curtis S, Chao Zhou, Feijun Luo, Likang Xu. The Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Overdose, Abuse, and Dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical Care, 2016; 54 (10): 901.

10Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK91497/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK91497.pdf.

11Beletsky, Leo, and Corey Davis; Today's fentanyl crisis: Prohibition's Iron Law, revisited, International Journal of Drug Policy 46 (2017) 156–159.

12Krishnamurthy et al., Impact of Urine Drug Screening on No Shows and Dropouts among Chronic Pain Patients: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Pain Physician. 2016 Feb; 19(2):89-100.

13Vadivelu, et. al; The Implications of Urine Drug Testing in Pain Management, Current Drug Safety 2010, 5 (267-270).

14Nahin, Richard; Estimates of Pain Prevalence and Severity in Adults: United States, 2012." The Journal of Pain: official Journal of the American Pain Society 16.8 (2015): 769–780. Studies using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey consistently estimated chronic pain (pain =3 months) prevalence at 13 to 15%. (Nahin 2012).

15Institutes of Medicine 2011 (p. 62).

16Boudreau, et al., Trends in De-facto Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain, Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 December; 18(12): 1166–1175. Note: the authors state that "Our results may not be generalizable to care delivered and/or financed in other types of health care systems and other regions of the US."

17Defined as episodes lasting longer than 90 days that had 120+ total days supply of dispensed medication or 10+ opioid prescriptions dispensed within a given year were classified as long-term opioid episodes. Boudreau et al., cited in Volkow and McLellan, Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain — Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies, N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1253-63.

18A review of the diagnostic accuracy of urine drug testing found that, in a worst case scenario, 32.9% of patients' specimens to the lab because of abnormal results. (Christo, et al., Urine Drug Testing In Chronic Pain, Pain Physician 2011; 14:123-143). Pollack, et al. (2001) reported a false positive rate of 7% for simple urine tests. Vadivelu, et al. reports that 11-21% of initial immunoassay tests are disproven by a followup GC/MS.

19Brahm, et al.; Commonly prescribed medications and potential false-positive urine drug screens; Am J Health-Syst Pharm—Vol 67 Aug 15, 2010, 1344-1350.

20Brahm, et al.

21Milone, Michael; Laboratory Testing for Prescription Opioids, J Med Toxicol. 2012 Dec; 8(4): 408–416.

22Standridge et al., Urine Drug Screening: A Valuable Office Procedure, Am Fam Physician. 2010 Mar 1; 81(5):635-640.

23CDC Guideline also only recommends initial drug testing before treatment and that clinicians "consider" drug testing annually thereafter. The CDC reports that this is a type B recommendation based on level 4 evidence. That is, they recommend that clinicians should retain the choice to make individual decisions on this issue because it is based on the lowest quality evidence.

24Unexpected results would include tests that are positive for non-prescribed or illicit drugs, and tests that are negative for expected prescription drugs.

25Addiction Doctor Mary McMasters estimates that GC/MS testing costs between $200 and $300. See also Vadivelu, et al.

26 In order to not abandon patients, doctors would likely provide referrals to other pain doctors and would give patients a "reasonable" amount of time to find another doctor. The doctors to whom such patients would be referred are under no obligation to treat them however.

27https://www.dhp.virginia.gov/medicine/newsletters/OpioidPrescribingBuprenorphine03142017.pdf.

28Krishnamurthy et al. found that administration of urine drug screens at a first doctor visit was associated with an increased rate of no-shows (23.75%) when compared to patients who did not undergo urine drug screens at a first doctor visit (10.24%). Krishnamurthy et al., "Impact of Urine Drug Screening on No Shows and Dropouts among Chronic Pain Patients: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study." Pain Physician. 2016 Feb; 19(2):89-100.

29http://townhall.virginia.gov/L/GetFile.cfm?File=C:\TownHall\docroot\\meeting\26\25243\Minutes_DHP_25243_v2.pdf.

30Beletsky, Leo, and Corey Davis; Today's fentanyl crisis: Prohibition's Iron Law, revisited, International Journal of Drug Policy 46 (2017) 156–159.

31Rhodes, Tim; Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: A rapidly changing risk environment, International Journal of Drug Policy 46 (2017) 107–111.

32https://departments.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2017/06/heroin_fentanyl_brochure.pdf.

33http://townhall.virginia.gov/L/GetFile.cfm?File=C:\TownHall\docroot\\meeting\26\25243\Minutes_DHP_25243_v2.pdf.

34http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Fatal-Drug-Overdoses-Quarterly-Report-Q1-2017_Updated.pdf.

35http://www.dfs.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CY16DfsDataReport_Final.pdf Slide 27.

36The term "substance misuse" is not defined in the proposed regulation.

Agency's Response to Economic Impact Analysis:

The Board of Medicine and the Department of Health Professions do not concur with the result of the economic impact analysis (EIA) that "there is insufficient data to accurately compare the magnitude of the benefits versus the costs." The focus of the analysis was on the cost of one requirement of regulation, urine drug screens. We believe the analysis failed to fully analyze the personal and societal costs of opioid addiction. It is the position of the agency that reducing the quantity of opioids in our homes and communities has already been shown to have a cost-benefit and will ultimately have a direct benefit in a reduction in opioid misuse and opioid overdose deaths.

1. The agency believes the analysis does not include sufficient data about the current crisis in opioid overdose deaths.

In 2015, there were 811 opioid deaths and in 2016, there were 1,133 – a 40% increase. In a preliminary report from the Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), the number for 2017 is expected to be 1,181. The result of the 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment notes that controlled prescription drugs have been linked to the largest number of overdose deaths of any illicit drug class since 2001. For each of these deaths, there are immeasurable costs. For the purpose of an economic analysis, medical malpractice carriers and civil litigants can attribute costs in dollars and cents for each year of life lost.

Yearly direct and indirect costs related to prescription opioids have been estimated (based on studies published since 2010) to be $53.4 billion for nonmedical use of prescription opioids; $55.7 billion for abuse, dependence (i.e., opioid use disorder), and misuse of prescription opioids; and $20.4 billion for direct and indirect costs related to opioid-related overdose alone. While we acknowledge that these are national figures, the EIA has used national data to extrapolate the costs of urine drug screens for Virginians. Copious amounts of data exist in national and state reports on the opioid crisis for which these regulations offer a partial solution.

2. The agency believes the analysis does not make the connection between the opioid crisis of fentanyl and heroin to the prescribing of opioid pain medication.

One of the primary purposes of these regulations is to reduce the number of persons who enter the pipeline of addiction through a legitimately prescribed opioid. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that a study of young, urban injection drug users interviewed in 2008 and 2009 found that 86% had used opioid pain relievers nonmedically prior to using heroin, and their initiation into nonmedical use was characterized by three main sources of opioids: family, friends, or personal prescriptions Examining national-level general population heroin data (including those in and not in treatment), nearly 80% of heroin users reported using prescription opioids prior to heroin.

The report from DCJS noted that "data from Department of Forensic Sciences (DFS) and Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) demonstrate that there are still a large number of individuals using prescription opioids non-medically. These individuals are at risk of overdose death through the prescription drugs they are currently using, but they are also at a higher risk of using heroin in the future. Although only a small percentage of individuals who abuse prescription opioids move on to heroin, a high percentage of heroin users report that their first opioid was a prescription drug (https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/researchreports/relationship-between-prescription-drug-abuse-heroin-use/). Additionally, non-medical users of prescription opioids may seek to acquire those drugs illegally, putting themselves at risk of purchasing and using counterfeit pills made with fentanyl and fentanyl analogs."

Data from OCME indicates that between 2013 and 2016, the number of prescription opioid fatalities involving fentanyl and/or heroin increased 69%. In 2016, 37% of prescription opioid fatalities also involved fentanyl and/or heroin. Although illicit fentanyl cases increased 207% between 2015 and 2016, there were almost four times as many heroin cases and four times as many prescription opioid cases that year.

Data from the Virginia Prescription Monitoring Program shows that since the adoption of emergency regulation there has been a drop in morphine milligram equivalents (MME). MME per day is the amount of morphine an opioid dose is equal to, often used to gauge the abuse and overdose potential of the amount of opioid being prescribed at a particular time. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that individuals taking greater than 90 MME/day are at a higher risk of overdose and death. The total number of patients prescribed high dosages declined from 169,145 individuals in the fourth quarter of 2016 to 137,618 individuals in the third quarter of 2017, or an 18.6% decline in individuals receiving greater than 100 MME/day. The data is an indicator of the effectiveness of the emergency regulation being replaced with the proposed regulations for which the EIA was prepared.

Numerous reports in the press have made the connection between the overdose death of a person who was prescribed on opioid following an accident or medical procedure. The intent of this regulation is to require prescribers to prescribe fewer quantities for shorter periods of time and to consider nonpharmacological alternatives or non-opioid medications that have the effect of addressing a patient's pain without the potential for addiction and long-term, costly consequences.

3. The agency believes the analysis has not included sufficient data on cost savings relating to a reduction on opioid prescribing.

For example, this agency provided information from the Department of Medical Assistance Services, which experienced a 44% decrease in opioid days-supply and 27% decrease in opioid prescription spending when that agency implemented the CDC guidelines on which these regulations were based, for an annual reduction in drug spending on opioids of approximately $466,000. It is that agency's belief that costs related to an increase in urine drug screens (which have been routinely required by pain management physicians prior to adoption of these regulations) would be more than offset by the decrease in spending on opioid prescriptions, so it would be budget neutral or result in a net cost savings.

Data from the Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) show that from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2017 pain reliever doses declined from 129,797,789 to 77,729,833, which represents a 40.15% decline. It is apparent that the emergency regulations are having a positive effect on the costs of prescription opioids – a cost benefit to consumers and insurers that could be reflected in the EIA.

4. There is an incorrect statement in the analysis about one regulatory requirement.

On pages 3 and 12 of the EIA, the analysis notes that the regulation requires prescribers to query the PMP for all individuals before prescribing an opioid. In fact, the regulation states that "the prescriber shall perform a history and physical examination appropriate to the complaint, query the Prescription Monitoring Program as set forth in § 54.1-2522.1 of the Code of Virginia…" Section 54.1-2522.1 requires a prescriber to query "at the time of initiating a new course of treatment to a human patient that includes the prescribing of opioids anticipated at the onset of treatment to last more than seven consecutive days." While the agency may believe a prescriber should query before prescribing on opioid for any period of time, that is not what the law and regulation require. It is required only if a prescription is being written "to last more than seven consecutive days."

Summary:

The proposed regulatory action adopts requirements for the prescribing of opioids and products containing buprenorphine as required by Chapters 291 and 682 of the 2017 Acts of Assembly. The regulations establish the practitioners to whom the regulations apply and the exceptions to or nonapplicability of the regulations. Regulations for the management of acute pain include requirements for the evaluation of the patient, limitations on quantity and dosage, and medical recordkeeping. Regulations for the management of chronic pain include requirements for evaluation and treatment, including a treatment plan; informed consent and agreement; consultation with other providers; and medical recordkeeping. Regulations for the prescribing of buprenorphine include requirements for patient assessment and treatment planning, limitations on prescribing the buprenorphine mono-product (without naloxone), dosages, co-prescribing of other drugs, consultation, and medical records for opioid addiction treatment. The regulation replaces emergency regulations currently in effect.

CHAPTER 21

REGULATIONS GOVERNING PRESCRIBING OF OPIOIDS AND BUPRENORPHINE

Part I

General Provisions

18VAC85-21-10. Applicability.

A. This chapter shall apply to doctors of medicine, osteopathic medicine, and podiatry and to physician assistants.

B. This chapter shall not apply to:

1. The treatment of acute or chronic pain related to (i) cancer, (ii) a patient in hospice care, or (iii) a patient in palliative care;

2. The treatment of acute or chronic pain during an inpatient hospital admission or in a nursing home or an assisted living facility that uses a sole source pharmacy; or

3. A patient enrolled in a clinical trial as authorized by state or federal law.

18VAC85-21-20. Definitions.

The following words and terms when used in this chapter shall have the following meanings unless the context clearly indicates otherwise:

"Acute pain" means pain that occurs within the normal course of a disease or condition or as the result of surgery for which controlled substances may be prescribed for no more than three months.

"Board" means the Virginia Board of Medicine.

"Chronic pain" means nonmalignant pain that goes beyond the normal course of a disease or condition for which controlled substances may be prescribed for a period greater than three months.

"Controlled substance" means drugs listed in The Drug Control Act (§ 54.1-3400 et seq. of the Code of Virginia) in Schedules II through IV.

"FDA" means the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

"MME" means morphine milligram equivalent.

"Prescription Monitoring Program" means the electronic system within the Department of Health Professions that monitors the dispensing of certain controlled substances.

"SAMHSA" means the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Part II

Management of Acute Pain

18VAC85-21-30. Evaluation of the acute pain patient.

A. Nonpharmacologic and non-opioid treatment for pain shall be given consideration prior to treatment with opioids. If an opioid is considered necessary for the treatment of acute pain, the practitioner shall give a short-acting opioid in the lowest effective dose for the fewest possible days.

B. Prior to initiating treatment with a controlled substance containing an opioid for a complaint of acute pain, the prescriber shall perform a history and physical examination appropriate to the complaint, query the Prescription Monitoring Program as set forth in § 54.1-2522.1 of the Code of Virginia, and conduct an assessment of the patient's history and risk of substance misuse.

18VAC85-21-40. Treatment of acute pain with opioids.

A. Initiation of opioid treatment for patients with acute pain shall be with short-acting opioids.

1. A prescriber providing treatment for acute pain shall not prescribe a controlled substance containing an opioid in a quantity that exceeds a seven-day supply as determined by the manufacturer's directions for use, unless extenuating circumstances are clearly documented in the medical record. This shall also apply to prescriptions of a controlled substance containing an opioid upon discharge from an emergency department.

2. An opioid prescribed as part of treatment for a surgical procedure shall be for no more than 14 consecutive days in accordance with manufacturer's direction and within the immediate perioperative period, unless extenuating circumstances are clearly documented in the medical record.

B. Initiation of opioid treatment for all patients shall include the following:

1. The practitioner shall carefully consider and document in the medical record the reasons to exceed 50 MME/day.

2. Prior to exceeding 120 MME/day, the practitioner shall document in the medical record the reasonable justification for such doses or refer to or consult with a pain management specialist.

3. Naloxone shall be prescribed for any patient when risk factors of prior overdose, substance misuse, doses in excess of 120 MME/day, or concomitant benzodiazepine are present.

C. Due to a higher risk of fatal overdose when opioids are prescribed with benzodiazepines, sedative hypnotics, carisoprodol, and tramadol, the prescriber shall only co-prescribe these substances when there are extenuating circumstances and shall document in the medical record a tapering plan to achieve the lowest possible effective doses if these medications are prescribed.

D. Buprenorphine is not indicated for acute pain in the outpatient setting, except when a prescriber who has obtained a SAMHSA waiver is treating pain in a patient whose primary diagnosis is the disease of addiction.

18VAC85-21-50. Medical records for acute pain.

The medical record shall include a description of the pain, a presumptive diagnosis for the origin of the pain, an examination appropriate to the complaint, a treatment plan, and the medication prescribed or administered to include the date, type, dosage, and quantity prescribed or administered.

Part III

Management of Chronic Pain

18VAC85-21-60. Evaluation of the chronic pain patient.

A. Prior to initiating management of chronic pain with a controlled substance containing an opioid, a medical history and physical examination, to include a mental status examination, shall be performed and documented in the medical record, including:

1. The nature and intensity of the pain;

2. Current and past treatments for pain;

3. Underlying or coexisting diseases or conditions;

4. The effect of the pain on physical and psychological function, quality of life, and activities of daily living;

5. Psychiatric, addiction, and substance misuse history of the patient and any family history of addiction or substance misuse;

6. A urine drug screen or serum medication level;

7. A query of the Prescription Monitoring Program as set forth in § 54.1-2522.1 of the Code of Virginia;

8. An assessment of the patient's history and risk of substance misuse; and

9. A request for prior applicable records.

B. Prior to initiating opioid treatment for chronic pain, the practitioner shall discuss with the patient the known risks and benefits of opioid therapy and the responsibilities of the patient during treatment to include securely storing the drug and properly disposing of any unwanted or unused drugs. The practitioner shall also discuss with the patient an exit strategy for the discontinuation of opioids in the event they are not effective.

18VAC85-21-70. Treatment of chronic pain with opioids.

A. Nonpharmacologic and non-opioid treatment for pain shall be given consideration prior to treatment with opioids.

B. In initiating and treating with an opioid, the practitioner shall:

1. Carefully consider and document in the medical record the reasons to exceed 50 MME/day;

2. Prior to exceeding 120 MME/day, the practitioner shall document in the medical record the reasonable justification for such doses or refer to or consult with a pain management specialist;

3. Prescribe naloxone for any patient when risk factors of prior overdose, substance misuse, doses in excess of 120 MME/day, or concomitant benzodiazepine are present; and

4. Document the rationale to continue opioid therapy every three months.

C. Buprenorphine mono-product in tablet form shall not be prescribed for chronic pain.

D. Due to a higher risk of fatal overdose when opioids, including buprenorphine, are given with other opioids, benzodiazepines, sedative hypnotics, carisoprodol, and tramadol, the prescriber shall only co-prescribe these substances when there are extenuating circumstances and shall document in the medical record a tapering plan to achieve the lowest possible effective doses of these medications if prescribed.

E. The practitioner (i) shall regularly evaluate the patient for opioid use disorder and (ii) shall initiate specific treatment for opioid use disorder, consult with an appropriate health care provider, or refer the patient for evaluation and treatment if indicated.

18VAC85-21-80. Treatment plan for chronic pain.

A. The medical record shall include a treatment plan that states measures to be used to determine progress in treatment, including pain relief and improved physical and psychosocial function, quality of life, and daily activities.

B. The treatment plan shall include further diagnostic evaluations and other treatment modalities or rehabilitation that may be necessary depending on the etiology of the pain and the extent to which the pain is associated with physical and psychosocial impairment.

C. The prescriber shall document in the medical record the presence or absence of any indicators for medication misuse or diversion and shall take appropriate action.

18VAC85-21-90. Informed consent and agreement for treatment for chronic pain.

A. The practitioner shall document in the medical record informed consent, to include risks, benefits, and alternative approaches, prior to the initiation of opioids for chronic pain.

B. There shall be a written treatment agreement signed by the patient in the medical record that addresses the parameters of treatment, including those behaviors that will result in referral to a higher level of care, cessation of treatment, or dismissal from care.

C. The treatment agreement shall include notice that the practitioner will query and receive reports from the Prescription Monitoring Program and permission for the practitioner to:

1. Obtain urine drug screens or serum medication levels when requested; and

2. Consult with other prescribers or dispensing pharmacists for the patient.

D. Expected outcomes shall be documented in the medical record including improvement in pain relief and function or simply in pain relief. Limitations and side effects of chronic opioid therapy shall be documented in the medical record.

18VAC85-21-100. Opioid therapy for chronic pain.

A. The practitioner shall review the course of pain treatment and any new information about the etiology of the pain and the patient's state of health at least every three months.

B. Continuation of treatment with opioids shall be supported by documentation of continued benefit from such prescribing. If the patient's progress is unsatisfactory, the practitioner shall assess the appropriateness of continued use of the current treatment plan and consider the use of other therapeutic modalities.

C. The practitioner shall check the Prescription Monitoring Program at least every three months after the initiation of treatment.

D. The practitioner shall order and review a urine drug screen or serum medication levels at the initiation of chronic pain management and at least every three months for the first year of treatment and at least every six months thereafter.

E. The practitioner (i) shall regularly evaluate the patient for opioid use disorder and (ii) shall initiate specific treatment for opioid use disorder, consult with an appropriate health care provider, or refer the patient for evaluation for treatment if indicated.

18VAC85-21-110. Additional consultations.

A. When necessary to achieve treatment goals, the prescriber shall refer the patient for additional evaluation and treatment.

B. When a prescriber makes the diagnosis of opioid use disorder, treatment for opioid use disorder shall be initiated or the patient shall be referred for evaluation and treatment.

18VAC85-21-120. Medical records for chronic pain.

The prescriber shall keep current, accurate, and complete records in an accessible manner readily available for review to include:

1. The medical history and physical examination;

2. Past medical history;

3. Applicable records from prior treatment providers or any documentation of attempts to obtain those records;

4. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and laboratory results;

5. Evaluations and consultations;

6. Treatment goals;

7. Discussion of risks and benefits;

8. Informed consent and agreement for treatment;

9. Treatments;

10. Medications (including date, type, dosage, and quantity prescribed and refills);

11. Patient instructions; and

12. Periodic reviews.

Part IV

Prescribing of Buprenorphine for Addiction Treatment

18VAC85-21-130. General provisions pertaining to prescribing of buprenorphine for addiction treatment.

A. Practitioners engaged in office-based opioid addiction treatment with buprenorphine shall have obtained a SAMHSA waiver and the appropriate U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration registration.

B. Practitioners shall abide by all federal and state laws and regulations governing the prescribing of buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

C. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners who have obtained a SAMHSA waiver shall only prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction pursuant to a practice agreement with a waivered doctor of medicine or doctor of osteopathic medicine.

D. Practitioners engaged in medication-assisted treatment shall either provide counseling in their practice or refer the patient to a mental health service provider, as defined in § 54.1-2400.1 of the Code of Virginia, who has the education and experience to provide substance misuse counseling. The practitioner shall document provision of counseling or referral in the medical record.

18VAC85-21-140. Patient assessment and treatment planning for addiction treatment.

A. A practitioner shall perform and document an assessment that includes a comprehensive medical and psychiatric history, substance misuse history, family history and psychosocial supports, appropriate physical examination, urine drug screen, pregnancy test for women of childbearing age and ability, a check of the Prescription Monitoring Program, and, when clinically indicated, infectious disease testing for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis.

B. The treatment plan shall include the practitioner's rationale for selecting medication-assisted treatment, patient education, written informed consent, how counseling will be accomplished, and a signed treatment agreement that outlines the responsibilities of the patient and the prescriber.

18VAC85-21-150. Treatment with buprenorphine for addiction.

A. Buprenorphine without naloxone (buprenorphine mono-product) shall not be prescribed except:

1. When a patient is pregnant;

2. When converting a patient from methadone or buprenorphine mono-product to buprenorphine containing naloxone for a period not to exceed seven days;

3. In formulations other than tablet form for indications approved by the FDA; or

4. For patients who have a demonstrated intolerance to naloxone; such prescriptions for the mono-product shall not exceed 3.0% of the total prescriptions for buprenorphine written by the prescriber, and the exception shall be clearly documented in the patient's medical record.

B. Buprenorphine mono-product tablets may be administered directly to patients in federally licensed opioid treatment programs. With the exception of those conditions listed in subsection A of this section, only the buprenorphine product containing naloxone shall be prescribed or dispensed for use off site from the program.

C. The evidence for the decision to use buprenorphine mono-product shall be fully documented in the medical record.

D. Due to a higher risk of fatal overdose when buprenorphine is prescribed with other opioids, benzodiazepines, sedative hypnotics, carisoprodol, and tramadol, the prescriber shall only co-prescribe these substances when there are extenuating circumstances and shall document in the medical record a tapering plan to achieve the lowest possible effective doses if these medications are prescribed.

E. Prior to starting medication-assisted treatment, the practitioner shall perform a check of the Prescription Monitoring Program.

F. During the induction phase, except for medically indicated circumstances as documented in the medical record, patients should be started on no more than eight milligrams of buprenorphine per day. The patient shall be seen by the prescriber at least once a week.

G. During the stabilization phase, the prescriber shall increase the daily dosage of buprenorphine in safe and effective increments to achieve the lowest dose that avoids intoxication, withdrawal, or significant drug craving.

H. Practitioners shall take steps to reduce the chances of buprenorphine diversion by using the lowest effective dose, appropriate frequency of office visits, pill counts, and checks of the Prescription Monitoring Program. The practitioner shall also require urine drug screens or serum medication levels at least every three months for the first year of treatment and at least every six months thereafter.

I. Documentation of the rationale for prescribed doses exceeding 16 milligrams of buprenorphine per day shall be placed in the medical record. Dosages exceeding 24 milligrams of buprenorphine per day shall not be prescribed.

J. The practitioner shall incorporate relapse prevention strategies into counseling or assure that they are addressed by a mental health service provider, as defined in § 54.1-2400.1 of the Code of Virginia, who has the education and experience to provide substance misuse counseling.

18VAC85-21-160. Special populations in addiction treatment.

A. Pregnant women may be treated with the buprenorphine mono-product, usually 16 milligrams per day or less.

B. Patients younger than the age of 16 years shall not be prescribed buprenorphine for addiction treatment unless such treatment is approved by the FDA.

C. The progress of patients with chronic pain shall be assessed by reduction of pain and functional objectives that can be identified, quantified, and independently verified.

D. Practitioners shall (i) evaluate patients with medical comorbidities by history, physical exam, appropriate laboratory studies and (ii) be aware of interactions of buprenorphine with other prescribed medications.

E. Practitioners shall not undertake buprenorphine treatment with a patient who has psychiatric comorbidities and is not stable. A patient who is determined by the prescriber to be psychiatrically unstable shall be referred for psychiatric evaluation and treatment prior to initiating medication-assisted treatment.

18VAC85-21-170. Medical records for opioid addiction treatment.

A. Records shall be timely, accurate, legible, complete, and readily accessible for review.

B. The treatment agreement and informed consent shall be maintained in the medical record.

C. Confidentiality requirements of 42 CFR Part 2 shall be followed.

D. Compliance with 18VAC85-20-27, which prohibits willful or negligent breach of confidentiality or unauthorized disclosure of confidential Prescription Monitoring Program information, shall be maintained.

VA.R. Doc. No. R17-5033; Filed November 4, 2017, 11:37 a.m.